AN ELUSIVE CHILDHOOD

Valentina Gueorguieva

editors: Ivan Elenkov and Daniela Koleva

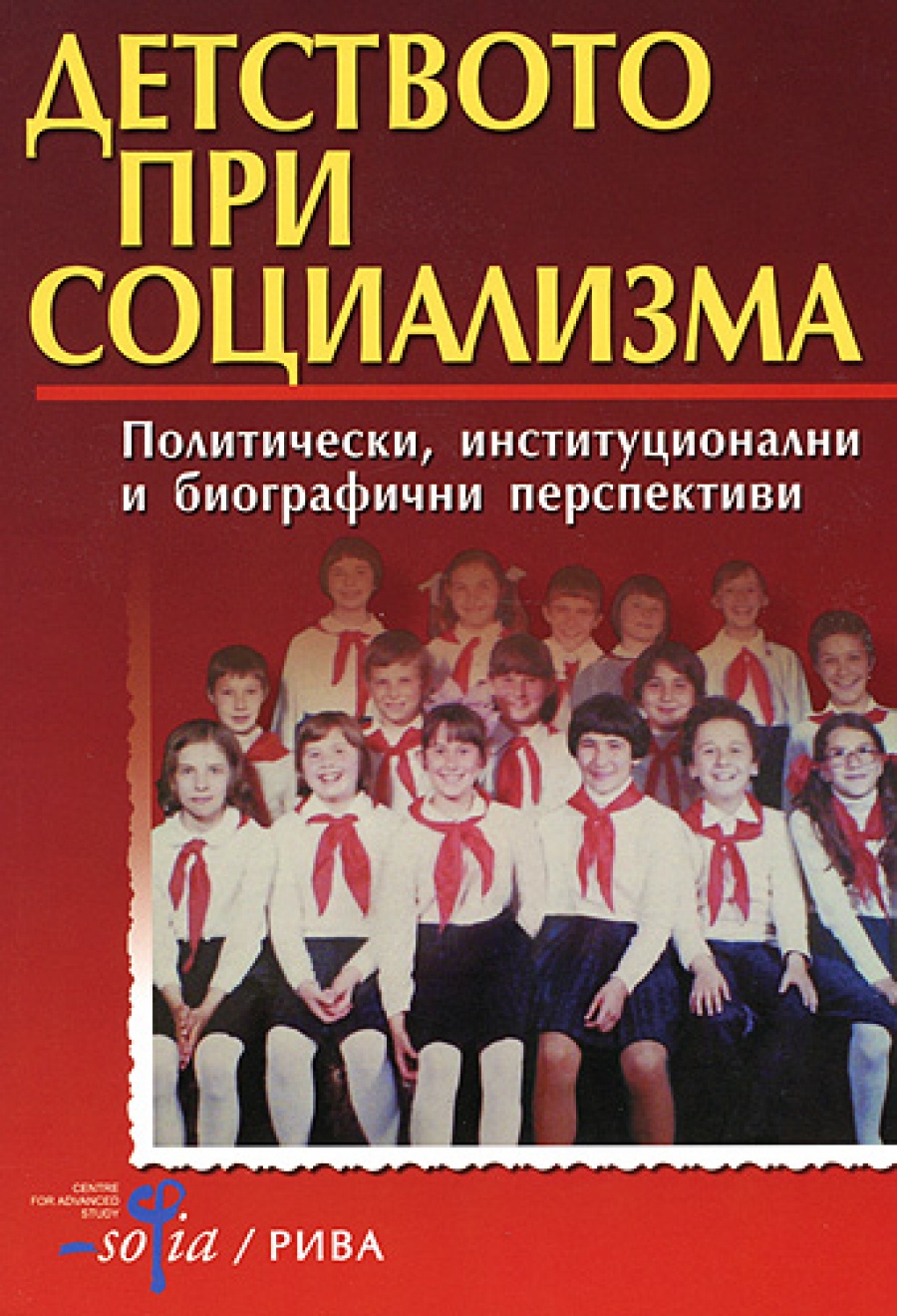

title: Childhood under Socialism.

Sofia: Centre for Advanced Study/Riva, 2010, pp.208.

Maybe because of my own memories, I approached the book Childhood under Socialism expecting to find a happy childhood in it too. I was in that highly sentimental mood of remembering, best illustrated by propositions such as ‘Whatever childhood memories you may have, they are always nice, sweet and true!’ (to quote a comment from the visitors’ book of the Inventory Storehouse of Socialism exhibition, p. 173).

As I read on, the book got me out of this uncritical mood by consistently confronting me with constructed models of a happy socialist childhood. If we provisionally divide the studies in the book into two parts, history and memory (this division is provisional insofar as participants’ memories are also used in the historical reconstructions), in the historical part childhood is represented through the social engineering of socialism (in the studies devoted to Pioneer leaders and to the Banner of Peace project); through the legislative initiatives in the first half of the twentieth century which substituted care for children with demographic and national policies; through the institutional structure of child care (in the studies on the homes for orphans and children with special needs before and after 1989); through the untimely maturity of participants in the brigadier (voluntary labour) movement. Here the world of childhood is elusive, having been substituted with political and institutional models.

In the second part devoted to childhood memories, instead of memories of games, fun and dreams of a bright future we again find justificatory narratives that are meant to make the past look more acceptable (p. 183), or uncertainty and confusion – the generational drama of those who remember their socialist childhood in rosy colours.

In short, childhood as a carefree time of growing up, fun and a bright vision of the future, is almost absent from the book. The theoretical part of the introduction, written by Kristina Popova, outlines the research field of childhood examined in the book: various issues related to the life of children (games, work, child care, juvenile crime), regional studies on childhood, on children from different social groups, generations, religious and ethnic communities.

The children of socialist Bulgaria are a vast subject that has been little explored, and the book is innovative in this respect. With the exception of Kristina Popova’s publications on childhood in the previous historical period, the subject of growing up in socialist Bulgaria is examined only in Karin Taylor’s studies which are devoted to the next age period and belong more to the field of youth cultures.[1] In the introduction, Kristina Popova traces the construction of ‘the idea of childhood as a sheltered period in the life of the individual’ (p. 11). The ideology of happy childhood was constructed in different ways before and after the First World War, and at the time of socialism.

In the paternalistic model of society under socialism, the idea about the right to happiness inherited from eighteenth-century thinkers was transformed into a prescription, into coercion to happiness. Notions of the future were invariably accompanied by the images of the happy socialist childhood with its sterilely attractive carefreeness and powerful propaganda effect. (p. 14)

The studies in the book are grounded on this assumption, both in the choice of subject matter and in the analysis of the source material. The first study does not only trace the statutory framework of ‘the creation of the new child’ of socialism as a task of the ubiquitous Pioneer Children’s Organization, it also describes the concrete techniques through which professionally trained Pioneer leaders had to ‘create’ Pioneer self-initiative (insofar as according to Nadezhda Krupskaya’s ideas, the Pioneer movement had to emerge and to be managed at the grassroots level, at the initiative of the children themselves); the techniques through which they had to arrange the ‘Pioneer Kingdom’ in the same way as they had to arrange Pioneer children into rows and columns, marching and singing in chorus; the techniques through which they had to stage childhood in the same way as they staged events from the heroic past.

In Ivan Elenkov’s reconstruction, the project on the creation of the Banner of Peace International Children’s Assembly again traces the techniques of childhood management, but in the period from around 1975 to 1984. Born of the ‘verbal ramblings’ (p. 63) of the then chairperson of the Committee for Art and Culture, Lyudmila Zhivkova, the project implemented the new ideology drawn by the regime from Zhivkova’s visions: ‘the promise of a new salvation based on culture, and a new human being reborn for beauty through culture’ (ibid.). Thus, children became a promise – the promise of the socialist versatile creative personality. They were as if always in embryo, always not fully developed, always an unfinished project. According to the Banner of Peace project, the trajectory of development of the child’s personality was exclusively in the sphere of high culture. Children were expected to create art organized in different forms depending on the forms of the high arts: painting, music, literature (pp. 58-59). Although the practical implementation of this ideological programme is not examined in this study, relevant excerpts from the minutes of the discussions on the ‘weaknesses’ in the organization of different events are aptly cited. The detailed reports on the expenditures provoke a crooked smile.

The next three studies describe the legislative and institutional care for children before, under, and after socialism, outlining an inevitable and alternativeless continuity. It turns out that the legislative initiatives devoted to children in the period between 1918 and 1944, which are studied by Sveta Balutsova, boiled down to measures to encourage large families, social measures aimed at particular target groups, where ‘children and the relevant laws turned out to be an instrument for strengthening domestic policy and statehood’ (p. 93). Thus, under socialism the institutional structure of ‘homes’ (Mother and Child Home, i.e. homes for children born out of wedlock, Home for Children and Adolescents, homes for disabled children, and so on ) resembled a network of Foucauldian disciplinary institutions, according to Anelia Kasabova’s account. They were closed, isolated and ineffective insofar as they produced non-independent individuals who needed to be cared for and ‘placed’ (in employment, housing, and so on) even after they came of age. Irina Radeva’s article discusses the problems in institutional child care after 1989, the legacy of the previous period, and the statutory framework. The second part of her study uses statements of experts and ‘stakeholders’ who can be made out in the author’s conclusions but who are not quoted systematically. In this way, childhood is viewed through a double veil: ‘children at risk’ are viewed first through the eyes of educators and experts, and then again through the author’s conclusions. The study occasionally relapses into project jargon.

The studies in this collection transcend not only the time frame of the socialist period but also the age frame of childhood – Bilyana Raeva’s study on the brigadier movement marks the boundaries of childhood.

Especially interesting are the last three studies, which provisionally belong to the section on memory of socialist childhood. It is here that the exposition acquires anthropological density and childhood can be felt in the naïve beauty of memories. We are speaking, of course, of representations. In the DDR Museum in Berlin the representations are game-like: ‘Open here’, ‘Touch this’. The museum exhibition features toys, Pioneer children, a school blackboard as well as punks, beer bottles, graffiti, locks of coloured hair. Socialism is infantilized, and its museumification is accused of normalization. Svetla Kazalarska’s analysis compares museum representations and public reactions in Germany and Bulgaria, and it is much more meticulous than I could possibly describe in this review.

Nadezhda Galabova works with interviews of alumni of the elite English Language High School in Sofia, which paint a suspiciously neat and representative picture of the past. The existence of schools for the elite in a society of equals must have obviously faced the said representatives of the elite with a test. They had to construct an acceptable image of their special place/school. The same strategies of representation are at work to the present day, creating ‘monolithic memorial constructions’ (p. 182) of the knowledge which such people had unquestionably acquired.

The last article discusses the childhood memories told by Bulgarians from two generations, those in their twenties and in their thirties, collected within the framework of the internet project I Lived Socialism devoted to ordinary people’s memories of socialist times. Diana Ivanova classifies the two age groups also as two types of attitudes towards the socialist childhood, two types of uncertainty and the dramas stemming from it: (a) ‘I rationally understand that socialism had to go, but I am emotionally confused: I don’t understand why my feelings from that time are wrong’ (p. 194); (b) according to the author, the older generation suffer from deeper traumas, they speak of shame and they are more self-reflexive.

If we must necessarily speak of dramas within the paradigm of memory, then I must say that in the last article I discovered the roots of my own drama, too. ‘But I remember my happy childhood,’ one of the contributors to the I Lived Socialism project exclaimed in dismay upon learning the well-kept family secret that one of his uncles had been sentenced to death and executed by the People’s Tribunal (p. 195). This made him feel guilty that he had lived happily without knowing the truth about the crimes of the regime. As a researcher, I know that happy childhood is an ideological construction. The studies in this book skillfully deconstruct the happy childhood under socialism. But the fact that I know it is a social construction does not make my happy childhood less real to me in my memories and experiences. That is also why my childhood will always elude all attempts at deconstruction.

[1] See Taylor, K. (2003) Socialist orchestration of youth: The 1968 Sofia Youth Festival and encounters on the fringe, Ethnologia Balkanica, 7/2003, pp. 43-61; Taylor, K. (2006) The ‘Sexual revolution’ in Bulgarian socialism, Balkanistichen Forum, 1-3/2006, pp. 159-178.

- Valentina Gueorguieva

- Childhood under Socialism